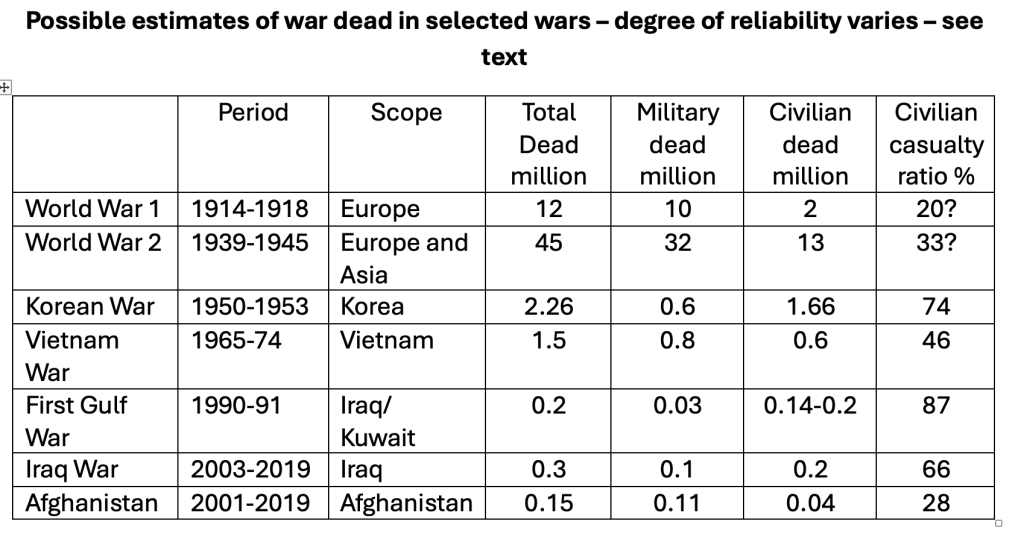

In recent wars 90% of people killed were NOT civilians. That is right – the widely quoted civilian casualty ratio of 90% of people killed in modern wars being civilians is a bulshit statistic. I am embarrassed to say that, once upon a time I was drawn to this statistic too. It is completely false. So what is the real figure and how do we use it to make sense of Gaza?

Civilians Dying in War

All statistics of war casualties and civilian causalities in particular are murky. This is especially the case for the side that suffers the most destruction and is the least developed. Poorer societies lack the means to count and what means they have are easily disrupted by physical, institutional, and human destruction.

How do civilians die in war? Their direct deaths arise from the way that they get caught up in war and are killed violently as collateral damage – think of a bombing campaign, or because they are directly targeted by the opposing armed forces whether official or auxiliaries. The line between collateral damage and direct targeting is fuzzy. In the last century killing civilians came to be seen as a legitimate part of warfare because civilians began to be defined as part of the war effort. Undermining civilian morale as a means of defeating the enemy was one of the factors that led to strategic bombing in World War 2. Some civilians worked directly in war supply. All could be thought of as combatants through their ‘support’ of war. This has continued in many wars since.

The second way that civilians die is indirectly as a result of hunger and disease and lack of medical care that can follow in the tracks of war. Historically the biggest number of civilian deaths has likely come from this source. But this also raises a problem of how we are also to define the geographic and temporal scope of war. Fighting can be precisely mapped and dated. After the last shot is fired, unless there is a state collapse, a relatively small number will continue to die as a result of wounds or unexploded munitions.

The impact of war on hunger and disease can spread widely. Should we include, for example, the victims of the Bengal famine in the civilian victims of World War 2? It will also be lagged and last much longer. The bigger number of deaths here may come after the formal fighting has ended. If you are interested you can read a paper I wrote on these problems.

Civilian deaths and asymmetric power

The potential loss of civilian life also reflects unequal power. The side with the greatest economic and military power will likely be able to inflict the greatest direct and indirect losses on civilians. The bigger the gap then potentially the bigger the civilian cost. Wars between advanced powers and poor ‘nations’ have been especially costly in these terms. Asymmetric power also affects how casualties are viewed. The greatest attention is likely to be paid to the losses of the big, advanced power.

Gaza and modern warfare

The origins of the current war in Gaza go back a long way. Since its establishment in 1948 Israel has acquired a huge and ever more sophisticated military presence. It has not only created imported weapons stockpiles but has its own domestically produced arms . A simple measure of the military power of Israel (although it still formally denies it) is that it has its own nuclear weapons.

Over time the sophistication and potential precision of Israeli arms has grown (though we should be cautious – the role of smart munitions is often exaggerated; smartness is ill-defined and smart munitions can have dumb controllers). Israel too has a massive surveillance capacity over Gaza and the West Bank. Gaza even had a population register which they were required to share with Israel. This means that much of the early destruction was likely targeted and deliberate.

By contrast the Palestinian side has been poorly armed despite much being made of their ability to construct rockets. This disparity can be seen in the historic imbalance in casualties that have arisen as a result of previous wars or ‘policing’ actions.

Counting the Dead in Gaza

The basic figures for Gaza dead and wounded come from the Ministry of Health in Gaza. The Israeli government says these cannot be trusted because it is a Hamas organisation. In the past, however, these figures have been broadly accepted. Israel’s supporters also dismiss UN figures claiming that their data is politically compromised.

The figures are what are called body count figures. Counting exploded bodies is not easy – nor is recording them. Bodies will be missed under rubble. Whose bodies they are will often not be known. Bodies may only be able to be classified in broader categories, male-female, rough age etc. This is made worse by what appears to be the deliberate targeting of all aspects of the civilian infrastructure. What we do not know is how many of these bodies are those of active combatants.

The Israeli government has not given its own estimates. But it insists that it has not been targeting civilians but Hamas combatants. It does not define these. Is a 14-year-old throwing a firework – a combatant? The logic of the official Israeli claims tends towards the idea that all males – teenagers and above – who have been killed were active Hamas combatants as were quite a few women.

So far, the basic numbers of 30,000 plus dead with a civilian casualty ratio of at least 2:1 or around 66% but possibly actually as high as 3 or 4: 1 with the majority of civilians killed women and children seems unassailable. It is what we might expect when a high-tech military power attacks a small densely populated area (Gaza is the size of greater Birmingham in the UK) with a largely defenceless and overwhelmingly civilian population. And after months of war in which people are now trying to survive in appalling conditions it is likely to grow higher as the impact of hunger and disease intensifies. As in any war when this affect kicks in the civilian casualty ratio will rise even more.